Imagine leaving England in the 1800s when realistically you knew you would never return

Francis John Blincoe (1789-1871) left England for New Zealand in 1841. He came from a family of shepherds and agricultural labourers who lived and worked in the area around Windsor, Eton and Clewer. He and his family had been booked to sail on the London in the middle of the year but failed to do so, very likely because he was still in Reading Gaol! He was probably imprisoned for debt rather than for a criminal office for the family's emigration had been recommended by their Methodist Minister. On Census night in 1841 he was recorded in gaol and his wife Anne and their children were in the Windsor Union Workhouse.

By December, Francis had been released and the family readied themselves to sail on the Clifford from the Port of London to Nelson in the north of New Zealand's South Island. This would have been a huge decision to make. The six surviving children who accompanied them were Anne 15, Sarah 13, Francis 11, John 7, William 5 and James not yet one.

On 13 December 1841 the emigrants were taken aboard. The following day the Clifford was towed downstream from Blackwall to Gravesend where she lay at moorings for five days, taking on stores and where the master, Captain Joseph Sharp, and the twelve cabin passengers came on board, most of whom were related to Joseph Somes, the Governor of the New Zealand Company.

On 18 December the Clifford was towed by a steamship downstream as far as the Downs and by early evening had arrived off Deal. The voyage proper began on 20 December and almost immediately most people, including the ship's doctor, were seasick, and many continued in this unhappy state for a week. However, by then some 200 miles off Portugal, things settled down and there was dancing and singing in the evening.

There were an unusual number of very small children on board, so when one family caught the measles it spread rapidly to other children and Dr Hughes decided that their mothers should have a daily allowance of a pint of porter. Francis' wife, Anne was one of the ten women listed.

It is not clear whether the migrants had paid for their passage or whether they were indentured to the New Zealand Company, but it seems that they were entitled to agreed amounts of rations for the voyage that were provided by the ship. It is recorded that they complained, 'that their allowance of potatoes should be cleaned of dirt before they were weighed,' and demanded that, 'their coffee be roasted before it was weighed' — these were thought to be 'absurd and unbecoming requirements'.

On New Year's Eve 'a dance was got up with an allowance of grog, and the glim being hoisted on deck fore and aft amidst much cheering and a very merry evening followed'. The weather continued fair with the ship making good progress, on some days averaging 10 knots. On 12 January they passed the coast of Sierra Leone. The Clifford was now entering the doldrums and encountered calms or very light southerly winds, making little progress between 9 January and the 14 February. Temperature rose to 84°F and 'a number of children became distressed with heat rash — they were ordered to be immersed in the deck tub every morning. At this stage Captain Sharp found it necessary to ration water down to 5 pints per day'. It was during this period that one of the cabin passengers gave birth to a baby son. The father had brought a cow along, presumably in case his wife's milk should fail. With the shortage of water, the cow collapsed and died.

The Clifford probably followed the usual course across the South Atlantic towards the coast of Argentina until they picked up the prevailing westerly winds. At any rate, by early March the winds freshened as they cleared the Cape of Good Hope and the voyage continued across the Southern Ocean. 'Passengers were treated to very brilliant displays of the Southern Lights'. By this time the southern winter was approaching and the ship was in the 'Roaring Forties'; it was so cold that the emigrants had to be persuaded by the doctor to go on deck for fresh air. With fewer deaths than births on the voyage the vessel actually delivered more people to New Zealand than had sailed from London. This was a remarkable record for the period; on the much shorter transatlantic voyages 10% mortality was common and sometimes rose to 40%.

The Clifford moored at Wellington on 5 May 1842. It does appear that the emigrants were contracted to the Company to proceed to Nelson, for special permission had to be sought for two families to go ashore and 'constables had to be posted by the gang-ways to ensure that no one escaped'. In spite of this, six of the crew jumped ship, several more attempted to do so and one of the migrants managed to make his escape, leaving his wife and possessions on board'. The vessel proceeded to Nelson and landed the emigrants there on 12 May after a voyage of four and a half months.

After such a successful voyage out, the Clifford met with disaster as she returned home. Sailing from Nelson for China on 16 May she struck a reef in the Bismarck Archipelago on 16 August and foundered.

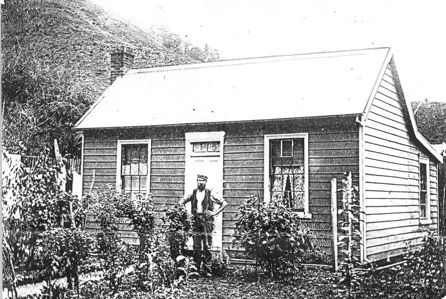

John Blincoe, grandson of Francis tending the garden in Nelson c.1910

Francis and Ann had another daughter, Emily, born in 1843; another baby son did not survive. As a settler (''squatter') in Nelson, Francis and his family lived at first in Nile Street where in 1845 he was recorded as a labourer. The eldest son Francis was in Haven Road working as a domestic servant. By 1849 the family was in nearby Selwyn Place and were tenants of a holding of four acres. Three acres were cleared and cultivated, half planted with wheat and half as gardens; they had four cattle and sixty goats. The house was of earth - presumably un-baked brick and had a shingled roof. From 1857 Francis and Ann owned a block of land in Kawai Street that passed to Francis junior when his father died in 1871.

When Francis emigrated he had been described as 'farmer, bricklayer's labourer', but he excelled as a gardener, a talent and enthusiasm that has been passed down the generations. Francis' grandson, John at 90 still lived alone, up keeping a quarter-acre garden and producing flowers and vegetables that he entered in horticultural shows. One of his brothers applied for a job as gardener at the Cathedral and was asked for his qualifications, he replied, "I'm a Blincoe", and was appointed!

Ref: June Neale, Pioneer Passages

Research by Pamela Blincoe

Sara-Anne Blincoe,

Auckland, New Zealand